The so-called ‘West Lothian question’ draws attention to the anomaly caused by asymmetric devolution, in which devolved legislatures have law-making powers for some parts of a country but the shared parliament is also solely responsible for government of part of the whole. In the UK, the anomaly arises because devolution is limited to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland (which therefore each have two parliaments governing them), while England is governed solely from Westminster. There is therefore a question of how to balance the democratic rights and representation of the various parts of the UK, when it is asymmetrically devolved.

This page tries to explain the nature of the problem, how it comes about, and to give a sense of how significant it is.

It is worth noting that this is an issue that concerns only the House of Commons. The House of Lords has no territorially-identifiable membership in the same way. Most of its members (all creations since 1801, including all life peers) are Peers of the United Kingdom. Some hereditary peers of older creation are Peers of England, Scotland or Great Britain (Irish peers have never had a right, as such, to sit in the Lords), but they are comparatively few in number.

Tam Dalyell and the West Lothian question

Since ‘home rule’ first came on the agenda in the 1880s, a form of what we call the West Lothian question has been debated. (Indeed, its logic was the reason Gladstone moved to embrace ‘home rule all round’.) For current purposes, it was first identified (and given its name) in the 1970s debates about devolution, which concerned much more limited assemblies for Scotland and Wales, by Tam Dalyell MP, who sat for West Lothian. In a telling speech in the second reading on the Scotland bill on 14 November 1977, he said

I shall spare the House alliterative lists of being able to vote on the gut issue of politics in relation to Birmingham but not Bathgate. The fact is that the question with which I interrupted the Prime Minister on Thursday about my voting on issues affecting West Bromwich but not West Lothian, and his voting on issues affecting Carlisle but not Cardiff, is all too real and will not just go away.

If these alliterative lists simply symbolised some technical problem in the Bill, the House could be certain that Ministers would have ironed it out since February, if for no other reason than to spare themselves from having to listen to grinding repetition from me. That alone would have been ample reward and would have made their work solving the West Lothian-West Bromwich problem worth while.

The truth is that the West Lothian-West Bromwich problem is not a minor hitch to be overcome by rearranging the seating in the devolutionary coach. On the contrary, the West Lothian-West Bromwich problem pinpoints a basic design fault in the steering of the devolutionary coach which will cause it to crash into the side of the road before it has gone a hundred miles.

(HC Debates 14 November 1977 vol 939 col 122)

On the level of democratic principle, the problem is a serious one, and innately insoluble. However, there is more to it in reality than that issue of principle.

Do Scottish (or Welsh) MPs make much difference in practice to the balance of power at Westminster?

For all the heat the West Lothian question attracts, the answer is ‘not much’. Since 1945, two governments – both weak and short-lived Labour ones – have had a majority on election in Parliament as a whole, but not among MPs for English seats. These were Harold Wilson’s first government elected in October 1964 (which lasted until March 1966; 16 months), and his third government elected in February 1974 (which lasted until October of that year). The first was a minority government, the second had a four-seat majority.

In reality, when Labour has won a majority across the UK it has usually also won one in England. (The concentration of Conservative support means that by definition they will only win a majority across the UK with a strong majority in England.)

During the ‘new Labour’ years (1997-2010), there were two bills – and three votes – where the government depended on Scottish MPs for its majority, thanks to back-bench rebellions. These votes were for the introduction of ‘foundation hospitals’ and deferred (‘top-up’) university tuition fees. Not only did the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats vote against these measures, but they implemented hugely reinforced versions of them after entering government in coalition in 2010.

These two cases do highlight the real political problem of the West Lothian question: the democratic anomaly that lies at its heart. In these instances, the opposition opposed the government’s legislation, even though they later adopted similar but more radical policies. There was also considerable opposition within Labour ranks, starting at grass-roots level, which meant many MPs were under considerable pressure from their constituencies to oppose the bills. English Labour MPs were torn between responding to pressure from their voters and local parties, and loyalty to the government and the whips. Scottish MPs had no such dilemma, as their constituents were indifferent to what might happen in England, so had little reason not to follow the party whip.

How different patterns of representation make the problem worse

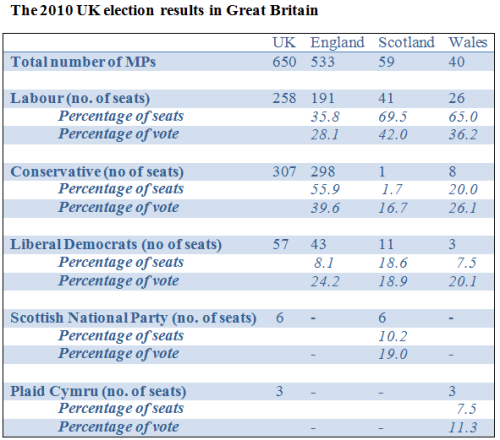

The West Lothian problem is made worse by differential representation across the four parts of the United Kingdom, in particular by the fact that Scotland elects a large number of Labour MPs (in the 2010 Parliament, 41 out of 59). Historically, that was further aggravated by over-representation of Scotland and Wales, but the number of Scottish MPs was reduced (from 72) at the 2005 election. To the extent Scotland is over-represented today, it is because it is so large and sparsely populated. (Wales remains over-represented compared to England. If the English criteria were applied, it would probably have about 32 MPs instead of 40.) The table below illustrates the problem of skewed representation thanks to the first-past-the-post electoral system:

The block of 41 Scottish Labour MPs (70 per cent of all Scottish MPs) are elected with only 42 per cent of the vote in Scotland. The 26 Welsh Labour MPs (65 per cent of the whole) are elected with only 36 per cent of the vote. It is therefore true that Labour benefits disproportionately from how the first-past-the-post electoral system works in Scotland and Wales; it gets a dominance in the number of MPs from there that its vote does not justify. But the converse is true in England. In the 2010 Parliament, the Conservatives won 56 per cent of seats with 40 per cent of the vote. (Labour also benefitted: 36 per cent of seats with 28 per cent of the vote.)

Equally, there are losers – quite apart from voters who get a UK Parliament that does not come close to corresponding to their collective preferences. In England and Wales (but not Scotland), the Lib Dems got far fewer MPs than their share of the vote justified. In Scotland, it was the Conservatives who were heavily under-represented, as were the nationalist parties in both Scotland and Wales.

The debate about electoral systems has been long and complex. All systems of proportional representation have their weaknesses as well as benefits. But any system of PR would also help redress this problem. While the parties talk about ‘fairness’, they overlook the unfairnesses built into an electoral system which they decline to contemplate changing.

Comparative context

It is notable that this problem is unique to the UK. Because other federal systems are formally symmetrical, or nearly so, it does not arise in countries like Canada, Switzerland, Australia or Germany. (In the US, it arises the other way around: the US Congress has power to legislate for ‘territories’, including Washington DC, that do not send members to Congress, though some do elect non-voting ‘delegates’.)

One of very few other countries in which it occurs is Denmark, where the two self-governing territories (Greenland and the Faroe Islands) are represented in the Danish Parliament as well, by members who take a full part in the Folketing’s work. But their representation is tiny: each has 2 members of the Folketing, so the anomaly relates to 4 members out of 179. Moreover, Greenland and the Faroes have their own party systems, so their members do not form part of the main Danish parties (though they align with the ideological blocks in the Folketing). Even then, the overall impact is negligible as each territory has elected one member who belongs to each of the ‘left’ and ‘right’ blocs.

Addressing the problem

The Conservative Party has long been concerned about the anomaly of the West Lothian question. Every Conservative UK general election manifesto since 2001 has included a commitment to introduce ‘English votes for English laws’, and in 2007 its Democracy Task Force chaired by the Rt Hon Kenneth Clarke MP published a report Answering the Question: Devolution, The West Lothian Question and the Future of the Union outlining proposals to implement that. (That report is no longer available on the Conservative Party website but can be found here.)

The Coalition’s Programme for Government contained a commitment to establish a commission to look into the issue, which was established in February 2012 under the chairmanship of Sir William McKay and which reported in March 2013. Its report can be found here.

Following the Scottish independence referendum, the UK Government announced that a Cabinet Committee on Devolution would be established, chaired by William Hague, Leader of the Commons. In December 2014, that committee’s work led to a paper (more green than white) on The Implications of Devolution for England, addressing issues of local and regional devolution as well as ‘English votes for English laws’ but reflecting stalemate between the Coalition parties on what to do. That can be found here.

(This page was updated on 17 December 2014.)

Pingback: New ‘page’ on the West Lothian question | DEVOLUTION MATTERS

Pingback: Constitutional reform following the Scottish referendum: a short reading list | Public law for everyone

Pingback: An ‘English rate of income tax’: six questions in search of an answer | DEVOLUTION MATTERS

Pingback: Revising for your 2015 Public Law exam? Here are some of this year’s key developments and blog highlights | Public law for everyone

Pingback: How Labour messed up 1998-model devolution | DEVOLUTION MATTERS